Wereldkinderen / Bureau Interlandelijke Adoptie (BIA) - Netherlands.

Please Note: If you are adopted through this KSS’ Partner Western Adoption Agency (in the time frames during which KSS worked with this Partner Western Adoption Agency) then you should initiate a Birth Family Search through KSS in Seoul. For KSS Adoptees ONLY, please see: Step by Step Korea Social Service (KSS) Birth Family Search.

SIA, Stichting Interlandelijke Adoptie

Netherlands' Foundation for Intercountry Adoption, likely referred to as NFIA on KSS Adoption Files

BIA, Bureau Interlandelijke Adoptie that merged with Wereldkinderen in 1983

If you are a Dutch KSS / Wereldkinderen Adoptee, we highly recommend starting a Birth Family Search with KSS in Seoul.

1969 or 1970 - 2006: KSS adopts to Wereldkinderen in the Netherlands. The vast majority of Dutch Adoptees are adopted through KSS.

According to a Dutch KSS Adoptee who spoke with Wereldkinderen in 2021:

”I recently asked Wereldkinderen about the reason for the termination of the cooperation of Wereldkinderen. They stated the reason: KSS did not want to provide insight into their finances. No transparency about this was the reason for Wereldkinderen to end the collaboration.”

*The earliest Dutch Korean adoptions were processed through Stichting Interlandelijke Adoptie (SIA), likely referred to as NFIA on KSS Adoption Files. SIA eventually became Bureau Interlandelijke Adoptie (BIA), which eventually merged with Wereldkinderen in 1983.

(Source: Bastiaan Flikweert, KSS Adoptees)

It is believed that a financial dispute between KSS and Wereldkinderen put a stop to their relationship in 2006.

(Source: KSS Adoptees)

It appears that the vast majority of Korean Adoptees in the Netherlands were adopted through KSS. It is believed that there are roughly 4,000 KSS Korean Adoptees adopted to the Netherlands.

(Source: KSS Adoptees, KSS Pamphlet)

Dutch KSS Korean Adoptees appear to have the most amount of information of any KSS Korean Adoptees sent to any of KSS’ other Partner Western Adoption Countries (including the US, Denmark, and Switzerland). Many Dutch KSS Korean Adoptees have “flight buddy” lists and the majority appear to have had real Korean Passports (real passport booklets as opposed to the one-page Travel Certificates which some Korean Adoptees have). It should be noted that both the Korean Passports and Korean Travel Certificates were one-way exit visas which were only good for the single use purpose of leaving Korea, and these documents have no validity today. However, these documents should, of course, be retained.

We believe that due to the fact that the Netherlands is a smaller, more tightly regulated country than the US, that likely Korean Adoptees sent from KSS to the Netherlands in many cases had more information (at least in terms of flight buddy lists - not necessarily in terms of biographical information) - than their US KSS Adoptee counterparts.

Anecdotally, it appears that many Dutch and Danish KSS Adoptees originated from Nam Kwang Orphanage in Busan. Nam Kwang Orphanage in Busan is still a functional orphanage, and you can schedule a file review with the Nam Kwang’s new Director. Find out more about Nam Kwang Orphanage’s contact information here. Please note that KSS Adoptees to the Netherlands (as with all other Western receiving countries) could have originated from many sources apart from Nam Kwang Orphanage in Busan.

Another orphanage which many Dutch KSS Adoptees seem to have originated from is Choon Hyun Babies Home in Gwangju (Jeolla Province). This is now a museum and the Director is Mrs. Hye Ryang YOO.

(Source: KSS Adoptees)

Dutch Korean Adoptees are encouraged to join the community on Facebook:

Arierang.nl

Through Google Translate:

“Mrs. (Syngman) Rhee secured the appointment of Mrs. Hong Oak Soon as director of a program of the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs and in 1954 the Child Placement Service was established. Another foreign adoption agency started through the Korean representative of International Social Service. This agency began operations in 1957 and merged with the Child Placement Service in July 1966. Mr. Harry Holt, an Oregon farmer and a staunch Christian, founded an adoption agency in 1955. The Catholic Relief Service has also worked in this area since 1955. The Korea Social Service began its relief work for mixed-blood children in 1965, under the direction of Mr. (Kun Chil) Paik, who is a graduate of the University of Minnesota School of Social Work and who was previously director of the Child Placement Service. Of the five agencies, the Child Placement Service and the Korea Social Service are indigenous organizations. The three others are foreign private initiative organizations. Of the full - Korean children placed, 90% have been placed through the Holt Adoption Program. Since 1965, the Child Placement Service has also played a major role in the placement of BL (Black?) - Korean children in Sweden. From 1962 to June 1969, the CPS placed 518 full Korean children in Swedish families. Holt Adoption Program placed 3,469 children during 1955-1966 and the number is now likely to exceed 4,000. Korea Social Service has engaged in the placement of mixed-blood children since 1965: 29 in 1965, 71 in 1966 and 83 in 1968. It is clear from the above that since 1962 the number of foreign adoptions has gradually increased. In connection with the amendment of the law , the number of adoptions shows a decrease for several years after 1962. While full-Korean adoptions tend to increase, despite…”

Source:

Book which many Dutch KSS Adoptees have: “After A Long Journey” by Elaine Reid and Hi Taik Kim

KSS Adoptees

+

Article:

'Give me one of those Koreans!'

Translation below via Google Translate:

'Give me one of those Koreans!'

Episode: 27 minutes

Reading time: 17 minutes

"Even if you save only one." These six words mark the beginning of international adoption in the Netherlands. They are spoken by writer Jan de Hartog, in a television interview with Mies Bouwman in 1967. After the Korean War (1950-1953), thousands of American soldiers were left behind as an occupying force under the UN flag. De Hartog talks about the inhumane conditions in which the children of these American soldiers and their Korean mothers find themselves. They are rejected by the family and have no future in their own country.

September 20, 2006

'Give me one of those Koreans!'

Watch Video

27 min

Driven by idealism, thousands of Dutch families respond to De Hartog's appeal and indicate that they want to adopt a Korean child. The 'adoptive Korean girl' is becoming a hype. Between 1970 and 1988, more than four thousand Korean children came to the Netherlands. Unprepared, full of enthusiasm, but also very naive, the first generation of foreign adopted children, now about 35,000, is welcomed. The wave of adoption from Korea comes to an abrupt end in 1988, when the Olympic Games are held in Seoul and the Korean government prefers to present a more modern image than 'child exporter' in the media. Other Times speaks with those involved from the very beginning. Marjory de Hartog, the writer's wife, parents, children, social workers. A broadcast about idealism,

Adoption wave

"Give me a Korean!"

"Even if you save only one." It is the spontaneous call for adoption from bestseller writer Jan de Hartog on the couch at Mies Bouwman. A phrase that, together with the images of his Korean daughters, unleashes a true wave of adoption in 1968. Thanks to the power of the TV screen, the Netherlands is under the spell of the underprivileged 'third world orphan' and the taboos surrounding adoption are disappearing like snow in the sun. The new phenomenon breathes the idealism of flower power. But the pink cloud won't last long...

This year it is fifty years ago that adoption in the Netherlands became legally possible. But despite the adoption of the Adoption Act in 1956, the taboos persisted. An adopted child aware of his status was the exception rather than the rule. Everything was allowed to hide the fact that in many cases the adoptive parents could not have children. Until the early 1970s, adopting children from third world countries became fashionable. Children whose appearance does not hide anything about their origin.

Jan de Hartog at Mies

'Even if you only save one'

The immediate reason for a real wave of adoption is the appearance of the popular writer Jan de Hartog in the television program Mies en scene by Mies Bouwman. A film crew has traveled to the United States for the successful broadway musical 'I do! I do!', an adaptation of De Hartog's play 'The canopy bed'. Afterwards, an interview with the 'writer in residence' himself is on the program. But those shots take an unexpected turn. A few days before, the writer couple took care of two Korean orphans and De Hartog called for help to the many thousands of foundlings and orphans in South-East Asia. Vietnam appeals to everyone's imagination, but the situation in South Korea is still dire, as he seems to want to impress upon television viewing the Netherlands.

Thousands of American soldiers remained in the area after the war (1950-1953) to maintain the status quo. The years of stationing have consequences: a considerable increase of 'half-breeds'. They are babies who are rejected. “Not only were they discriminated against, they simply didn't exist,” says Liesbeth Graatsma, social worker and contact mediator for Korea in the 1970s. “Koreans didn't have a population registry like here, but a family registry that was managed for the family eldest. Such a person would never accept an illegitimate child. Those children simply had no future.”

The Quakers, a religious community to which De Hartog belonged, are one of the driving forces behind the adoption of these children in the United States. There it is the famous writer Pearl Buck, who sets the 'good example' with six adopted children. Marjory, Jan de Hartog's English wife, reads a book about Buck's adoption work. She is so impressed by this that she wants to start taking care of orphans herself when the Vietnam War breaks out. “I started peddling to all kinds of organizations that they should pay attention to these children. Especially in Vietnam,” recalls Marjory de Hartog. But it wasn't until 1975 that peace was signed in Vietnam, and few were allowed access before that time. The couple gets involved with Buck's volunteer organization.

Not much later, the Korean Eva and Julia figure in Mies Bouwman's broadcast. Two cheerful preschoolers in a sun-drenched American suburb. There is no better advertisement imaginable for adoption. But De Hartog's flaming argument also helps. 'Even if you only save one', is such a statement that has an impact. And then something happens that nobody cares about. The telephone at the VARA does not stop ringing after the broadcast. “We didn't know when it aired, but suddenly in the middle of the night the phone rang. Mies was on the phone hysterically,” recalls Marjory de Hartog. “She didn't know what to do with all those phone calls: 'What do we tell those people? Can they call you?' was her question.” In total, that evening and the following days, more than a thousand people called for 'a little Korean'.

Sang and An de Klonia

Vietnam, the pill, the social assistance law

Plenty of reasons for a child from abroad

How can a spontaneous statement in one television program spark such a massive reaction? In 1967, growing criticism of the Vietnam War dominates the era. Television brings the war into the living room and millions of families are witnessing the horrors, especially the images of overcrowded children's homes and neglected, malnourished children.

In the meantime, the number of adoptions in the Netherlands is declining due to the introduction of the pill in 1962, which reduces the number of unwanted pregnancies, and the new General Assistance Act in 1963. This guarantee of a minimum subsistence level for every citizen leads to a decrease in the number of distant children. In more and more cases, the social services advise young unmarried mothers to raise their children themselves.

The Adoption Act (1956), which was introduced relatively late in the Netherlands, essentially meant that in a legal sense the adopted child becomes the full child of the adoptive parents. Until 1978, however, the biological parents retained the right to reverse the renunciation of their child through the courts. According to F. ten Siethoff, then secretary of the Adoption Council, an advisory committee for the Ministry of Justice and the court, it was one of the reasons for moving abroad. “It was the threat that the real parent would put up a barrier. With a child from afar, the family is also a bit further away.”

When it gradually becomes clear what the wars in Southeast Asia mean to tens of thousands of displaced children, little more is needed than an emotional speech from a popular speaker. A new social phenomenon is emerging: the adoption of third world children.

In a Korean hut

Polder idealism

'Full is full'

An action committee will be set up with the aim of starting aid for children in need. Foreign adoption is just one of the means. But the efforts are politically sensitive. “In the Netherlands, the argument was that the country was too full. There was serious fear of a wave of immigration,” says Marjory de Hartog. F. ten Siethoff, former secretary of the Adoption Council, also remembers reticence at the Ministry of Justice. “Guidelines were drawn up. It stated, among other things, that you were not allowed to admit the child if it was not certain that the distance had been properly arranged. There was also a whole bureaucracy involved. In practice, this meant that it was difficult to keep those children here. This put a brake on the unbridled entry.”

But the ministry also had moral concerns. There was a fear that bringing children from a completely different culture to the Netherlands would lead to all kinds of problems. The transition could be much too big and all kinds of difficulties in the parenting situation were predicted. They also feared child trafficking. Ten Siethoff: “Looking back, society presented us with a fait accompli. There were all those private initiatives. Practice has caught up with us. Nothing had been arranged. They just came in with those kids. And you couldn't send them back either."

“I remember a fortress consisting of rows of small houses. It was primitive, I slept on a mat and when there was food we ate rice, just rice. I remember having a great time there until Grandma got sick and couldn't take care of me anymore. Then I had to cook for her. Once upon a time, a woman would come by who was said to be working in Seoul. I think she was my mother. But if you ask me, did you know at that moment that that woman was your mother, then I say no. She came too little for that. I never knew my father. He was probably back to the US before I was born.”

These are the words of Sang de Klonia, now thirty-nine, and one of the first hundred children from South Korea to be adopted in the Netherlands. He's four when he comes. “It was my first time in the car and my first time on the plane. It was really an outing with other children. A nice day until we arrived in the reception hall at Schiphol. I thought something isn't right here. This is wrong.” Social worker Liesbeth Graatsma supervises the flights over time. “The journey took almost 32 hours. You had been with those children for a long time and then you kind of bond. Often those children had played wonderfully on the way, but they got stressed out at Schiphol. We tried to keep them calm, but if such a child continues to panic, there is only one solution: get the children and parents out of the car as quickly as possible.”

As easily as the first children, once at Schiphol, were pushed into a new life, their arrival was so precarious with the authorities. Political pressure eventually had to make the government acquiesce. Erie den Doolaard is the personification of this lobby. She is the wife of De Hartog's good friend and colleague A. den Doolaard. The residence of the writers' couple in the Veluwe serves as a temporary postal address for the many letters that pour in after De Hartog's appeal. Not only she, but also Mies Bouwman, receive loads of letters from parents who want to make themselves available. One of them is An de Klonia, Sang's adoptive mother: “Dutch children were not in stock and then this came our way and we thought bingo! So that was sign up and see what happens. Because at that time they were not allowed to enter the Netherlands at all.

Long waiting times

Marcel van Dam became ombudsman for the VARA in 1971. After many letters from complaining parents, he devotes several episodes to the complicated adoption procedure, which also caused a stir in the House of Representatives. The attitude of the ministry is a thorn in the side of D'66 MP Bert Schwarz, according to the parliamentary debate of January 1972: 'The Netherlands is relatively rich and absolutely full, like a tram can be full, in which everyone is normally admitted without discrimination. . But when the tram is full, no one is allowed in. (…) The government has done almost nothing to curb the immigration of foreign workers. The Department of Justice does make a contribution to curbing the immigration flow, which I do not appreciate, namely limiting the admission of foreign foster children.”

In 1967, the year that De Hartog made his appeal to Mies Bouwman, more than eighty percent of the total number of adopted children was of Dutch descent. Eight years later, almost half of the children placed are of foreign descent and more than one third are Korean. But demand exceeds supply. Parents have to wait endlessly before they can adopt a child. First there is the waiting period for the family survey, then there is the waiting period for the actual adoption. In some cases, it can be up to 7 years. An de Klonia has to wait 3.5 years for her Sang. “Yes, that waiting, that was a difficult period. The age difference with our first child started to play a role. That's why we preferred a slightly older child. Then the difference wasn't that big with our first."

Korea

Exporter of babies

In the following years, Korea's international adoption program has grown in popularity. Started as an initiative to rescue rejected mixed-race children, international adoption is evolving into a last resort for middle-class childless parents in Europe and the US. The Vietnam War puts the problem of third world children on the map. An de Klonia and her husband also participate in protests against the war. “We were anti-militarist yes. We were there from the first demonstrations,” says De Klonia. “It's always the damn soldiers who cause the kids. That also happened in the Netherlands with the Germans and the Canadians.” However, Vietnam will not grant entry until after 1975 when the peace is signed. That is why they move to another country.

In these years, international adoption has become almost synonymous with adoption from Korea, where the lines are short and the authorities cooperate well. But the country does not want to do business with Erie Den Doolaard. Because she is 'a housewife in the Veluwe', as Will Schütte recalls. “That wasn't official enough. A real body had to be created.” Wil Schütte is commissioned to set up a Foundation for Intercountry Adoption (SIA). Until then, she is an employee at FIOM, the Federation of Institutions for Unmarried Mother Care, which until then had been in charge of adoption. For a long time, adoption was inherent in the care of unmarried mothers.

But times are changing and Schütte is told by her boss: "Wouldn't you like to work with the SIA?" and he adds: “But then you have to arrange the financing yourself.” Schütte lobbies here and there in her husband's network, a high-ranking official in the Defense Department, and in her own network. She says she arranges a generous arrangement at KLM to get the children here as cheaply as possible and she also knows how to exert her influence on the Ministry of Justice. “I think those men thought, well that woman must also have something to do. In the beginning, everything really went smoothly. Nobody knew how to do it.” She rents an attic in the Haagse Schoolstraat. She gets the rattan chairs from her own house. A 'friend' gives her binders and she arranges a generous arrangement with KLM to fly the children over as cheaply as possible. Schutte: “We entered everywhere and we often left the meeting with big promises. They thought it was a whim of bored housewives. Adoption today, next year something different. But that turned out differently.”

Sang as a teenager

The Disillusionment of the Eighties

'Ray laserus in the cell'

It became clear in the course of the eighties that the criticized reticence of the Ministry of Justice also has another, more valid reason. The Netherlands now has more than 13,000 children from the Third World who have been adopted by Dutch parents. The babies and toddlers from the boom of the time are the adolescents of the eighties. The media creates a picture of problem cases because disappointed parents of children who have been removed from home seek publicity. Sang is also removed from home. “At one point it went wrong. Petty crime and stuff,” An recalls. She addresses Sang: “Until you were in the cell and the police came to your door. That really was the last straw. Then they made an emergency recording of it.” Sang: “I was untenable and unmanageable. In hindsight, that had everything to do with my adoption. It is underestimated what it means to come here from an Eastern culture. The idea was and is that you automatically do better here.”

Nevertheless, Liesbeth Graatsma, who has been involved in the SIA as a social worker from the very beginning, emphasizes that in many cases things went well. But she has to agree that in those first years there was too much optimism about the progress of the adoption. “We all thought those children are in a bind and there are no solutions in the country of origin. We did have that here. So we wanted to help those kids. We thought: it will take some getting used to, but it will work. With patience and love you will get there. That is what was later called the pink cloud.”

Korean baby at Schiphol

The Olympics of '88

The straw that broke the camel's back

Due to the negative media coverage, the positive image of international adoption is changing and the number of adoption applications is falling sharply. Between 1980 and 1989 even by sixty percent. In addition to the critical voices in the press, the first results of research into adoption mention special parenting problems for adoptive parents. The economic conditions are also less positive: the first major round of government cutbacks is underway.

But not only the demand, but also the supply is declining. In Asian countries, the political attitude towards adoption is changing. The increased standard of living in Korea, from $248 per capita in 1970 to $2,268 in 1987, goes hand in hand with growing self-awareness. Domestic adoption is being stimulated and there is a stronger call for an end to the 'export of babies'.

In Korea, this trend is marked by the 1988 Olympics. A year before the world spotlight is turned on Korea, a political upheaval takes place. In June 1987, student protests, strikes and a massive uprising herald the end of 25 years of military rule. The new freedom of expression offers room for a critical voice, but the adoptions continue unabated. One year later at the Games in Seoul, Korea proudly presents itself as a new industrialized democracy. But Western journalists seize the opportunity to paint a different picture of the country, presenting Korea as the world's largest exporter of children. It is the drop that makes the camel overflow. Not a single child disappears across the border during the Games. And the following year, the number of adoptions dropped significantly. In the Netherlands from 107 placements in 1988 to 13 in 1989. Korea seems to have lost its image as a baby exporter. During the 1990s, the Netherlands saw a slight revival in the number of adoption applications. In the meantime, China takes the cake. But every year a limited number of Koreans still await a new life in the Netherlands.

Sang de Klonia

The numbers

Research into behavioral problems

In 1979, research into the adoption of foreign children is presented for the first time in the Netherlands. Prof. dr. Dr René Hoksbergen, professor by special appointment of Adoption, mentions specific parenting problems in his book 'Adoption of children from distant countries'. But there are no firm conclusions because the children concerned have not yet arrived in our country. It was not until the late 1980s that the first major national study by child psychiatrist Frank Verhulst was published. His findings clearly reveal the problems: foreign adopted children come into contact with the police and the judiciary four times as often compared to 'ordinary children', they follow special education three times as often, the number of out-of-home placements is six times higher and a quarter has professional need help.

Yet researchers also contradict each other. Such as professor Femmie Juffer, herself an adoptive parent, who presented research results last year aimed at putting an end to the many myths surrounding the subject. She argues that foreign adopted children may have more behavioral problems than non-adopted children, but that the margins are small. Prof. dr. Hoksbergen regularly seeks publicity to point out the 'scale and intensity of behavioral and parenting problems'. According to him, these are 'many times larger than in children born in the Netherlands'. He still advocates better aftercare.

But those who really know are the nearly 35,000 foreign children who have been, or are being, raised by Dutch parents. Of these, 4,099 come from Korea. To Sang de Klonia, when one of the first asked the question: Is it pleasant to be adopted? "I wouldn't have had to. If only I had left me there. What would have happened then is a difficult question. I probably would have been dead. But the issue is what's worse: dying of hunger or dying of grief."

Text and research: Ariane Kleijwegt

Director: Hein Hoffmann

Editing: Laura van Hasselt

'Doe mij maar zo'n Koreaantje!' / "Give me one of those Koreans!"

Below is a new translation via ChatGPT of the following Dutch article:

Doe mij maar zo'n Koreaantje!' ('Give me one of those Koreans!')

Please note that we have alternated the original Dutch text first with the ChatGPT English translation following each section of Dutch:

Aflevering: 27 minuten

Leestijd: 17 minuten

'Al red je er maar één'. Deze zes woorden markeren het begin van de internationale adoptie in Nederland. Ze worden uitgesproken door schrijver Jan de Hartog, in een televisie-interview met Mies Bouwman in 1967. Na de Koreaanse oorlog (1950-1953) zijn duizenden Amerikaanse soldaten achtergebleven als bezettingsmacht onder VN vlag. De Hartog spreekt over de onmenselijke omstandigheden waarin de kinderen van deze Amerikaanse soldaten en hun Koreaanse moeders verkeren. Ze worden verstoten door de familie en hebben geen enkele toekomst in eigen land.

20 september 2006

'Doe mij maar zo'n Koreaantje!'

Bekijk Video

19 min

Gedreven door idealisme reageren duizenden Nederlandse gezinnen op de oproep van De Hartog en geven aan een Koreaans kind te willen adopteren. Het 'adoptie-Koreaantje' wordt een hype. Tussen 1970 en 1988 komen ruim vierduizend Koreaanse kinderen naar Nederland. Onvoorbereid, vol enthousiasme, maar ook zeer naïef wordt de eerste generatie buitenlandse adoptiekinderen, nu zo'n 35.000, verwelkomd. De adoptiegolf uit Korea komt in 1988 tot een abrupt einde, als de Olympische spelen in Seoel worden gehouden en de Koreaanse overheid liever met een wat moderner imago dan 'kinderexporteur' in de media komt. Andere Tijden spreekt met betrokkenen van het eerste uur. Marjory de Hartog, de vrouw van de schrijver, ouders, kinderen, maartschappelijk werkers. Een uitzending over het idealisme, het amateurisme en de roze wolk van de beginjaren van de internationale adoptie.

Adoptiegolf

‘Doe mij maar een Koreaantje!’

‘Al red je er maar één’. Het is de spontane oproep tot adoptie van bestseller-schrijver Jan de Hartog op de bank bij Mies Bouwman. Een zin die samen met de beelden van zijn Koreaanse dochtertjes in 1968 een ware adoptiegolf ontketent. Dankzij de macht van de beeldbuis raakt Nederland in de ban van het kansarme ‘derdewereld-weesje’ en de taboes rond adoptie verdwijnen als sneeuw voor de zon. Het nieuwe fenomeen ademt het idealisme van de flower power. Maar de roze wolk houdt niet lang stand...

Dit jaar is het vijftig jaar geleden dat adoptie in Nederland juridisch mogelijk werd. Maar ondanks de invoering van de adoptiewet in 1956 bleven de taboes bestaan. Een geadopteerd kind dat op de hoogte was van zijn status, was eerder uitzondering dan regel. Alles was geoorloofd om te verbergen dat de adoptie-ouders in veel gevallen geen kinderen konden krijgen. Totdat begin jaren zeventig het adopteren van kinderen uit derdewereldlanden is zwang raakt. Kinderen van wie het uiterlijk niets verhult over de afkomst.

~

"Give me one of those Koreans!"

Episode: 27 minutes

Reading time: 17 minutes

"Even if you can only save one." These six words mark the beginning of international adoption in the Netherlands. They are spoken by writer Jan de Hartog in a television interview with Mies Bouwman in 1967. After the Korean War (1950-1953), thousands of American soldiers remained as occupying forces under the UN flag. De Hartog talks about the inhumane conditions in which the children of these American soldiers and their Korean mothers find themselves. They are rejected by their families and have no future in their own country.

September 20, 2006

"Give me one of those Koreans!"

Watch Video

19 minutes

Driven by idealism, thousands of Dutch families respond to De Hartog's call and express their desire to adopt a Korean child. The 'adoption Korean' becomes a hype. Between 1970 and 1988, over four thousand Korean children come to the Netherlands. The first generation of foreign adoptees, now about 35,000, is welcomed unprepared, full of enthusiasm, but also very naive. The adoption wave from Korea comes to an abrupt end in 1988 when the Olympic Games are held in Seoul, and the Korean government prefers to present a more modern image than that of a 'child exporter' in the media. Andere Tijden (Other Times) speaks with those involved from the early days: Marjory de Hartog, the writer's wife, parents, children, and social workers. A program about idealism, amateurism, and the honeymoon phase of international adoption.

Adoption Wave

"Give me a Korean!"

"Even if you can only save one." It is the spontaneous call for adoption by best-selling author Jan de Hartog on the couch with Mies Bouwman. A sentence that, together with the images of his Korean daughters in 1968, unleashes a true adoption wave. Thanks to the power of television, the Netherlands becomes fascinated with the disadvantaged "third-world orphan," and the taboos surrounding adoption vanish into thin air. This new phenomenon embodies the idealism of the flower power era. But the honeymoon phase does not last long...

This year marks fifty years since adoption became legally possible in the Netherlands. However, despite the adoption law being implemented in 1956, the taboos persisted. An adopted child who was aware of their status was more of an exception than the rule. Everything was permissible to hide the fact that in many cases, adoptive parents couldn't have children. It wasn't until the early 1970s that adopting children from third-world countries gained popularity. Children whose appearance revealed nothing about their origin.

~

Jan de Hartog bij Mies

‘Al red je er maar één’

Directe aanleiding voor een heuse adoptiegolf is het optreden van de populaire schrijver Jan de Hartog in het televisieprogramma Mies en scene van Mies Bouwman. Een filmploeg is naar de Verenigde Staten afgereisd vanwege de succesvolle broadway-musical ‘I do! I do!’, een bewerking van De Hartog’s toneelstuk ‘Het hemelbed’. Aansluitend staat een interview met de ‘writer in residence’ zelf op het programma. Maar die opnames nemen een onverwachte wending. Enkele dagen ervoor heeft het schrijversechtpaar de zorg voor twee Koreaanse weesjes op zich genomen en promt roept De Hartog op tot hulp aan de vele duizenden vondelingen en weeskinderen in Zuid-Oost Azië. Vietnam spreekt tot ieders verbeelding maar ook in Zuid-Korea is de situatie nog steeds schrijnend, zo lijkt hij televisiekijkend Nederland op het hart te willen drukken.

Duizenden Amerikaanse soldaten zijn na de oorlog (1950-1953) in het gebied gebleven om de status quo te handhaven. De jarenlange stationering heeft consequenties: een flinke aanwas van ‘halfbloedjes’. Het zijn baby’s die verstoten worden. “Ze werden niet alleen gediscrimineerd, ze bestonden eenvoudigweg niet,” zegt Liesbeth Graatsma, maatschappelijk werkster en in de jaren zeventig contactbemiddelaar voor Korea. “Koreanen kenden geen bevolkingsregistratie zoals hier, maar een familieregistratie die beheerd werd voor de familie-oudste. Zo iemand zou nooit een buitenechtelijk kind accepteren. Die kinderen hadden eenvoudigweg geen toekomst.”

De Quakers, een religieuze gemeenschap waartoe De Hartog behoorde, zijn in de Verenigde Staten één van de drijvende krachten achter de adoptie van deze kinderen. Daar is het de beroemde schrijfster Pearl Buck, die met zes geadopteerde kinderen het ‘goede voorbeeld’ geeft. Marjory, de Engelse echtgenote van Jan de Hartog, leest een boek over het adoptiewerk van Buck. Ze is hier zo van onder de indruk dat ze bij het uitbreken van de Vietnamoorlog zelf werk wil maken van de opvang van weesjes. “Ik ben bij allerlei organisaties gaan leuren dat ze aandacht moesten schenken aan deze kinderen. Vooral ook in Vietnam,” herinnert Marjory de Hartog zich. Maar pas in 1975 wordt in Vietnam de vrede getekend, en voor die tijd krijgen weinigen toegang. Het echtpaar raakt betrokken bij de vrijwilligersorganisatie van Buck. En voor ze er erg in hebben heeft huize De Hartog er twee Koreaanse zusjes er.

Niet veel later figureren de Koreaanse Eva en Julia in de uitzending van Mies Bouwman. Twee vrolijke kleuters in een zonovergoten Amerikaanse buitenwijk. Er is geen betere reclame denkbaar voor adoptie. Maar het vlammende betoog van De Hartog helpt ook. ‘Al red je er maar één’, wordt zo’n uitspraak die impact heeft. En dan gebeurt er iets waar niemand rekening mee houdt. De telefoon bij de VARA houdt na de uitzending niet op met rinkelen. “We wisten niet wanneer het uitgezonden werd, maar plotseling ging midden in de nacht de telefoon. Mies hing hysterisch aan de lijn,” herinnert Marjory de Hartog zich. “Ze wist niet wat ze moest met al die telefoontjes: ‘Wat vertellen we die mensen? Kunnen ze naar jullie bellen?’ was haar vraag.” In totaal bellen die avond en de dagen daarop ruim duizend mensen voor ‘een Koreaantje’.

~

Jan de Hartog on Mies

"Even if you can only save one."

The direct trigger for a real adoption wave is the appearance of popular writer Jan de Hartog on the television program Mies en scene hosted by Mies Bouwman. A film crew has traveled to the United States due to the successful Broadway musical 'I do! I do!' which is an adaptation of De Hartog's play 'The Marriage Bed'. Following that, an interview with the 'writer in residence' himself is scheduled. But those recordings take an unexpected turn. A few days earlier, the writer couple took on the care of two Korean orphans, and promptly De Hartog calls for help for the thousands of foundlings and orphans in Southeast Asia. Vietnam captures everyone's imagination, but the situation in South Korea is still dire, or so it seems he wants to impress upon the Dutch television audience.

After the war (1950-1953), thousands of American soldiers remained in the region to maintain the status quo. The years of deployment have consequences: a significant increase in "half-breeds." These are babies who are abandoned. "They were not only discriminated against, they simply did not exist," says Liesbeth Graatsma, a social worker and contact mediator for Korea in the 1970s. "Koreans didn't have a population registration like here, but a family registration managed by the family elder. Someone like that would never accept an illegitimate child. Those children simply had no future."

The Quakers, a religious community to which De Hartog belonged, are one of the driving forces behind the adoption of these children in the United States. It is the famous writer Pearl Buck, with her six adopted children, who sets the "good example." Marjory, Jan de Hartog's English wife, reads a book about Buck's adoption work. She is so impressed by it that she wants to take action herself for the reception of orphans when the Vietnam War breaks out. "I went around to various organizations, pleading with them to pay attention to these children. Especially in Vietnam," Marjory de Hartog recalls. But it is not until 1975 that peace is signed in Vietnam, and few are granted access before that. The couple becomes involved in Buck's volunteer organization. And before they know it, they have two Korean sisters in their home.

Not long after, Korean Eva and Julia appear in the broadcast of Mies Bouwman. Two cheerful toddlers in a sun-drenched American suburb. There is no better advertisement for adoption. But De Hartog's passionate speech also helps. "Even if you can only save one" becomes a statement that has an impact. And then something happens that no one expected. The phone at VARA (Dutch broadcasting organization) keeps ringing after the broadcast. "We didn't know when it would be aired, but suddenly the phone rang in the middle of the night. Mies was hysterically on the line," Marjory de Hartog remembers. "She didn't know what to tell all those callers: 'What do we tell those people? Can they call you?' was her question." That evening and in the following days, over a thousand people call for 'a little Korean.'

~

Sang en An de Klonia

Vietnam, de pil, de bijstandswet

Redenen te over voor een kindje uit het buitenland

Hoe kan een spontane uitspraak in één televisieprogramma zo’n massale reactie ontketenen? In 1967 domineert groeiende kritiek op de Vietnamoorlog het tijdsbeeld. De televisie brengt de oorlog in de huiskamer en miljoenen gezinnen zijn getuige van de verschrikkingen, waarbij vooral de beelden van overvolle kindertehuizen en verwaarloosde, ondervoede kinderen enorm aangrijpen.

Ondertussen neemt in eigen land het aantal adopties af door de introductie van de pil in 1962, waardoor het aantal ongewenste zwangerschappen vermindert, en de nieuwe Algemene Bijstandswet in 1963. Deze garantie van een bestaansminimum voor iedere burger leidt tot een daling van het aantal afstandskinderen. In steeds meer gevallen adviseert de hulpverlening jonge ongehuwde moeders hun kind zelf op te voeden.

De adoptiewet (1956), die in Nederland relatief laat geïntroduceerd wordt, betekende in de kern dat het geadopteerde kind in juridische zin volledig kind van de adoptie-ouders wordt. Toch behielden de biologische ouders tot 1978 het recht om het afstand doen van hun kind via de rechter terug te draaien. Volgens F. ten Siethoff, destijds secretaris van de Adoptieraad, een adviescommissie voor het ministerie van Justitie en de rechtbank, was het één van de redenen om naar het buitenland uit te wijken. “Het was de dreiging dat de echte ouder een belemmering zou opwerpen. Met een kind van ver is de familie ook wat verder weg.”

Als langzamerhand duidelijk wordt wat de oorlogen in Zuid-Oost Azië betekenen voor tienduizenden ontheemde kinderen is er weinig meer nodig dan een emotioneel betoog van een populaire spreker. Een nieuw maatschappelijk fenomeen doet zijn intreden: de adoptie van derdewereldkinderen.

In een Koreaanse hut

~

Sang and An from Klonia

Vietnam, the pill, the welfare law

Plenty of reasons for a child from abroad

How can a spontaneous statement in one television program trigger such a massive response? In 1967, growing criticism of the Vietnam War dominates the zeitgeist. Television brings the war into people's living rooms, and millions of families witness the horrors, particularly the images of overcrowded orphanages and neglected, malnourished children are extremely poignant.

Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, the number of adoptions is decreasing due to the introduction of the birth control pill in 1962, which reduces the number of unwanted pregnancies, and the new General Assistance Act in 1963. This guarantee of a minimum subsistence level for every citizen leads to a decline in the number of children placed for adoption. In an increasing number of cases, social services advise young unmarried mothers to raise their children themselves.

The adoption law (1956), introduced relatively late in the Netherlands, meant that the adopted child legally becomes the full child of the adoptive parents. However, until 1978, biological parents retained the right to reverse the relinquishment of their child through the courts. According to F. ten Siethoff, former secretary of the Adoption Council, an advisory committee for the Ministry of Justice and the judiciary, this was one of the reasons for turning to foreign adoption. "There was the threat that the biological parent would raise obstacles. With a child from afar, the family is also a bit further away."

As it gradually becomes clear what the wars in Southeast Asia mean for tens of thousands of displaced children, little more is needed than an emotional speech from a popular speaker. A new social phenomenon emerges: the adoption of third-world children.

In a Korean hut.

~

Polderidealisme

‘Vol is vol’

Er komt een actiecomité met als doel de hulpverlening op gang te brengen voor kinderen in nood. Buitenlandse adoptie is slechts één van de middelen. Maar politiek liggen de inspanningen gevoelig. “In Nederland was het argument dat het land te vol was. Er was serieuze angst voor een immigratiegolf,” zegt Marjory de Hartog. Ook F. ten Siethoff, oud-secretaris van de Adoptieraad, herinnert zich terughoudendheid op het ministerie van Justitie. “Er werden richtlijnen opgesteld. Daarin stond ondermeer dat je het kind niet mocht opnemen als niet zeker was dat de afstand goed geregeld was. Verder kwam er een hele bureaucratie bij kijken. In de praktijk betekende dit dat het moeilijk was die kinderen hier te houden. Zo kwam er een rem op de ongebreidelde binnenkomst.”

Maar het ministerie had ook morele bezwaren. De vrees bestond dat kinderen uit een geheel andere cultuur naar Nederland halen tot allerlei problemen zou leiden. De overgang zou veel te groot kunnen zijn en allerlei moeilijkheden in de opvoedsituatie werden voorspeld. Ook vreesde men voor kinderhandel. Ten Siethoff : “Achteraf gezien werden we vanuit de samenleving voor een voldongen feit gesteld. Er waren al die particuliere initiatieven. De praktijk heeft ons ingehaald. Er was niets geregeld. Men kwam gewoon met die kinderen binnen. En je kon ze ook niet terugsturen.”

“Ik herinner me een vesting die bestond uit rijen kleine huisjes. Het was er primitief, ik sliep op een matje en als er al eten was aten we rijst, alleen maar rijst. Ik weet nog dat ik het er prima naar mijn zin had totdat oma ziek werd en niet meer voor mij kon zorgen. Toen moest ik voor haar koken. Er kwam wel eens een vrouw langs, waarvan men zei dat ze in Seoul werkte. Ik denk dat zij mijn moeder was. Maar als je me vraagt wist je op dat moment dat die vrouw je moeder was, dan zeg ik nee. Daarvoor kwam ze te weinig. Mijn vader heb ik nooit gekend. Die was waarschijnlijk al terug naar de VS, voordat ik geboren werd.”

~

Polder idealism

"Enough is enough"

An action committee is formed with the aim of initiating assistance for children in need. International adoption is just one of the means. However, there are political sensitivities surrounding these efforts. "In the Netherlands, the argument was that the country was already too full. There was serious fear of an immigration wave," says Marjory de Hartog. F. ten Siethoff, former secretary of the Adoption Council, also recalls the hesitancy at the Ministry of Justice. "Guidelines were established, stating, among other things, that a child should not be taken in if it was not certain that the relinquishment was properly arranged. Additionally, a whole bureaucracy was involved. In practice, this made it difficult to keep these children here. Thus, there was a curb on uncontrolled entry."

However, the ministry also had moral objections. There was concern that bringing children from a completely different culture to the Netherlands would lead to various problems. The transition could be too significant, and difficulties in the upbringing situation were predicted. There was also a fear of child trafficking. Ten Siethoff says, "In hindsight, we were confronted by a fait accompli from society. There were already those private initiatives. Reality caught up with us. Nothing was regulated. People simply arrived with those children, and you couldn't send them back."

"I remember a fortress consisting of rows of small houses. It was primitive; I slept on a mat, and if there was any food, we ate rice, only rice. I still remember that I was quite content until my grandma became ill and could no longer take care of me. Then I had to cook for her. Occasionally, a woman would come by, and they said she worked in Seoul. I think she was my mother. But if you ask me if I knew at that moment that she was your mother, I would say no. She didn't come often enough. I never knew my father. He was probably already back in the US before I was born."

~

Aan het woord is Sang de Klonia, nu negenendertig, en één van de eerste honderd kinderen uit Zuid-Korea die in Nederland worden geadopteerd. Hij is vier als hij komt. “Ik zat voor het eerst in de auto en voor het eerst in het vliegtuig. Het was echt een uitje met andere kinderen. Een leuke dag totdat we in de ontvangsthal op Schiphol kwamen. Ik dacht hier klopt iets niet. Dit is foute boel.” Maatschappelijk werkster Liesbeth Graatsma begeleidt in de tijd de vluchten. “De reis duurde bijna 32 uur. Je was lang met die kinderen geweest en dan krijg je toch een beetje een band. Vaak hadden die kinderen heerlijk gespeeld onderweg maar schoten ze op Schiphol in de stress. We probeerden ze rustig te houden, maar als zo’n kind blijft panieken dan is er maar één oplossing: kinderen en ouders zo snel mogelijk naar de auto wegwerken.”

Zo gemakkelijk als de eerste kinderen, eenmaal op Schiphol, een nieuw leven in werden ingeduwd, zo precair lag hun komst bij de autoriteiten. Politieke druk moest de overheid uiteindelijk doen inschikken. Erie den Doolaard is de verpersoonlijking van deze lobby. Zij is de vrouw van De Hartogs goede vriend en collega A. den Doolaard. Het verblijf van het schrijversechtpaar op de Veluwe fungeert als tijdelijk postadres voor de vele brieven die na De Hartogs oproep binnenstromen. Niet alleen zij, maar ook Mies Bouwman, ontvangen ladingen brieven van ouders die zich beschikbaar willen stellen. Eén van hen is An de Klonia, de adoptiemoeder van Sang: “Nederlandse kinderen waren niet in voorraad en toen kwam dit op onze weg en wij dachten bingo! Dus dat was aanmelden en kijken wat er gaat gebeuren. Want ze mochten toen helemaal Nederland nog niet binnen. We hadden al een kind, maar waren overtuigd dat we iets moesten doen om er tenminste één te redden..”

~

Speaking is Sang de Klonia, now thirty-nine years old and one of the first one hundred children from South Korea to be adopted in the Netherlands. He was four years old when he arrived. "It was my first time in a car and my first time on an airplane. It was really an outing with other children. A fun day until we arrived in the arrival hall at Schiphol. I thought something was wrong. This is bad news." Social worker Liesbeth Graatsma accompanied the flights during that time. "The journey lasted almost 32 hours. You had spent a long time with those children, and you develop a bit of a bond. Often, the children had played happily during the journey, but they became stressed at Schiphol. We tried to keep them calm, but if a child keeps panicking, there is only one solution: to quickly get the children and parents into the car."

As easily as the first children were pushed into a new life once they arrived at Schiphol, their arrival was precarious with the authorities. Political pressure eventually forced the government to give in. Erie den Doolaard personifies this lobby. She is the wife of De Hartog's good friend and colleague, A. den Doolaard. The residence of the writing couple in Veluwe serves as a temporary mailing address for the many letters that arrive after De Hartog's call. Not only she, but also Mies Bouwman, receives loads of letters from parents who want to offer themselves. One of them is An de Klonia, the adoptive mother of Sang. "Dutch children were not available, and then this came our way, and we thought, bingo! So we signed up and waited to see what would happen. Because at that time, they still couldn't enter the Netherlands at all. We already had a child, but we were convinced that we had to do something to save at least one."

~

Lange wachttijden

Marcel van Dam is in 1971 ombudsman voor de VARA. Na vele brieven van klagende ouders wijdt hij meerdere afleveringen aan de ingewikkelde adoptieprocedure, die ook tot ophef leidt in de Tweede Kamer. De opstelling van het ministerie is D’66 Kamerlid Bert Schwarz een doorn in het oog, zo blijkt uit het kamerdebat van januari 1972: ‘Nederland is relatief rijk en absoluut vol, zoals een tram vol kan zijn, waarin iedereen normaal zonder discriminatie wordt toegelaten. Maar als de tram vol is mag er niemand meer in. (…) Aan het afremmen van de immigratie van buitenlandse werknemers heeft de regering nog vrijwel niets gedaan. Wel levert het Departement van Justitie een bijdrage tot het indammen van de immigratiestroom, die ik niet waardeer, namelijk het beperken van de toelating van buitenlandse pleegkinderen.”

In 1967, het jaar dat De Hartog zijn oproep doet bij Mies Bouwman, is nog meer dan tachtig procent van het totaal aantal geadopteerde kinderen van Nederlandse afkomst. Acht jaar later is bijna de helft van de geplaatste kinderen van buitenlandse afkomst en ruim éénderde Koreaans. Maar de vraag overtreft het aanbod. Ouders moeten eindeloos wachten voordat ze een kindje kunnen adopteren. Eerst is er de wachttijd voor het gezinsonderzoek, dan is er de wachttijd voor de feitelijke adoptie. In sommige gevallen kan die oplopen tot 7 jaar. An de Klonia moet 3,5 jaar wachten op haar Sang. “Ja, dat wachten, dat was een moeilijke periode. Het leeftijdsverschil met ons eerste kind begon een rol te spelen. Daarom wilden we toen liever een wat ouder kind. Dan was het verschil niet zo groot met onze eerste.”

~

Long waiting times

In 1971, Marcel van Dam serves as the ombudsman for VARA. After receiving numerous letters from complaining parents, he dedicates several episodes to the complex adoption procedure, which also sparks controversy in the Dutch Parliament. The stance of the Ministry is a source of irritation for D'66 Member of Parliament Bert Schwarz, as evident from the January 1972 debate: "Netherlands is relatively rich and absolutely full, like a tram that can be full, in which everyone is normally admitted without discrimination. But if the tram is full, no one else is allowed in. (...) The government has hardly done anything to slow down the immigration of foreign workers. However, the Ministry of Justice contributes to curbing the immigration flow, which I do not appreciate, namely by limiting the admission of foreign foster children."

In 1967, the year De Hartog makes his appeal on Mies Bouwman's show, more than eighty percent of the total number of adopted children in the Netherlands are of Dutch origin. Eight years later, almost half of the placed children are of foreign origin, with over one-third being Korean. However, the demand exceeds the supply. Parents have to wait endlessly before they can adopt a child. First, there is the waiting time for the family assessment, and then there is the waiting time for the actual adoption. In some cases, this can take up to 7 years. An de Klonia has to wait for 3.5 years to adopt her Sang. "Yes, that waiting, it was a difficult period. The age difference with our first child started to become a factor. That's why we preferred to adopt a slightly older child. Then the age gap wouldn't be so significant with our first child."

~

Korea

Exporteur van baby’s

In de daarop volgende jaren maakt Korea’s internationale adoptieprogramma een grote populariteit door. Begonnen als initiatief om verstoten kinderen van gemengd ras te redden, ontwikkelt internationale adoptie zich tot een laatste uitvalsbasis voor kinderloze ouders uit de middenklassen in Europa en de VS. De Vietnamoorlog zet het probleem van de derdewereld-kinderen op de kaart. Ook An de Klonia en haar man lopen mee in protesten tegen de oorlog. “We waren anti-militaristisch ja. Vanaf de eerste demonstraties waren we erbij,” zegt De Klonia. “Het zijn verdomme altijd de militairen die de kinderen veroorzaken. Dat is in Nederland ook gebeurd met de Duitsers en de Canadezen.” Vietnam verleent echter pas toegang na 1975 als de vrede is getekend. Daarom wijkt men uit naar een ander land.

Internationale adoptie wordt in deze jaren haast synoniem aan adoptie vanuit Korea, waar de lijntjes kort zijn en de autoriteiten goed meewerken. Maar het land wil geen zaken doen met Erie Den Doolaard. Want ze is ‘een huisvrouw op de Veluwe’, zo herinnert Will Schütte het. “Dat was niet officieel genoeg. Er moest een heuse instantie in het leven worden geroepen.” Wil Schütte krijgt de opdracht een Stichting voor Interlandelijke Adoptie (SIA) op te richten. Tot die tijd is ze medewerkster bij FIOM, de Federatie Instellingen Ongehuwde Moederzorg, die tot dan toe belast is geweest met adoptie. Lang was adoptie immers inherent aan de zorg voor ongehuwde moeders.

Maar de tijden veranderen en Schütte krijgt van haar baas te horen: “Zou jij niet met de SIA aan de slag willen?” en hij voegt er aan toe: “Maar dan moet je zelf de financiering regelen.” Schütte lobby’t her en der in het netwerk van haar man, een hoge ambtenaar bij Defensie, en in haar eigen netwerk. Bij de KLM regelt ze naar eigen zeggen een riante regeling om de kinderen zo goedkoop mogelijk hier te krijgen en ook op het ministerie van Justitie weet ze haar invloed te laten gelden. “Ik denk dat die mannen hebben gedacht, ach dat vrouwtje moet ook wat te doen hebben. In het begin ging alles echt op zijn janboerenfluitjes. Niemand wist hoe het moest.” In de Haagse Schoolstraat huurt ze een zolder. De rotanstoeltjes haalt ze uit haar eigen huis.Van een ‘vrindje’ krijgt ze multomappen en bij de KLM regelt ze een riante regeling om de kinderen zo goedkoop mogelijk over te vliegen. Schutte:” We kwamen overal binnen en vaak verlieten we de vergadering weer met grote toezeggingen. Ze dachten dat het een bevlieging van verveelde huisvrouwen was. Vandaag adoptie, volgend jaar weer wat anders. Maar dat liep anders.”

~

Korea

Exporter of babies

In the following years, Korea's international adoption program gains significant popularity. Started as an initiative to rescue abandoned children of mixed race, international adoption evolves into a last resort for childless middle-class parents in Europe and the US. The Vietnam War brings the issue of third-world children to the forefront. An de Klonia and her husband also participate in protests against the war. "Yes, we were anti-militaristic. We joined the demonstrations from the very beginning," says De Klonia. "Damn it, it's always the military who cause the children. The same happened in the Netherlands with the Germans and the Canadians." However, Vietnam only allows access after 1975 when peace is established. Therefore, they turn to another country.

During these years, international adoption becomes almost synonymous with adoption from Korea, where the connections are strong, and the authorities cooperate well. But the country doesn't want to deal with Erie Den Doolaard because she is "a housewife on the Veluwe," as Will Schütte recalls. "That wasn't official enough. A proper organization needed to be established." Wil Schütte is tasked with creating the Foundation for Inter-Country Adoption (SIA). Until then, she works for FIOM, the Federation of Unmarried Mother Care Institutions, which has been responsible for adoption. Adoption has long been associated with the care of unmarried mothers.

But times are changing, and Schütte is told by her boss, "Wouldn't you like to work on the SIA?" and he adds, "But then you have to arrange the financing yourself." Schütte lobbies here and there within her husband's network, a senior civil servant in Defense, and her own network. She claims to have arranged a generous agreement with KLM to bring the children here as cheaply as possible, and she also manages to exert her influence at the Ministry of Justice. "I think those men thought, ah, that little lady needs something to do too. In the beginning, everything was really haphazard. No one knew how to do it." She rents an attic on Schoolstraat in The Hague. She brings rattan chairs from her own home. She receives folders from a friend, and she secures a generous arrangement with KLM to fly the children here as cheaply as possible. Schütte says, "We got access everywhere, and we often left the meetings with significant commitments. They thought it was a whim of bored housewives. Today adoption, next year something else. But it turned out differently."

~

Sang als puber

De desillussie van de jaren tachtig

‘Straallazerus in de cel’

Dat de bekritiseerde terughoudendheid van het Ministerie van Justitie ook een andere, meer gegronde reden heeft, blijkt in de loop van de jaren tachtig. Nederland kent inmiddels ruim 13.000 kinderen uit de Derde Wereld die door Nederlandse ouders zijn geadopteerd. De baby’s en kleuters uit de hausse van toen, zijn de pubers van de jaren tachtig. Via de media ontstaat een beeld van probleemgevallen doordat ontgoochelde ouders van uit huis geplaatste kinderen de publiciteit zoeken. Ook Sang wordt uit huis geplaatst. “Op een gegeven moment ging het mis. Kleine criminaliteit enzo,” herinnert An zich. Ze richt zich tot Sang: “Tot je straallazerus in de cel zat en de politie hier aan de deur kwam. Dat is echt de druppel geweest. Toen hebben ze er een spoedopname van gemaakt.” Sang: “Ik was onhoudbaar en onhandelbaar. Dat had achteraf gezien alles met mijn adoptie te maken. Het wordt onderschat wat het betekent om vanuit een Oosterse cultuur hier naar toe te komen. De gedachte was en is dat je het hier automatisch beter doet.”

Toch benadrukt Liesbeth Graatsma, vanaf het eerste uur als maatschappelijk werkster betrokken bij de SIA, dat het in veel gevallen wel goed is gegaan. Maar dat er in die eerste jaren een te groot optimisme is geweest over het verloop van de adoptie, moet ze beamen. “We dachten allemaal die kinderen zitten in de knel en in het land van herkomst zijn er geen oplossingen. Die hadden we hier wel. Dus we wilden die kinderen helpen. We dachten: het is even wennen, maar het gaat wel lukken. Met geduld en liefde dan kom je er wel. Dat is wat later de roze wolk werd genoemd.”

~

Sang as a teenager

The disillusionment of the 1980s

"Drunk as a skunk in the cell"

It becomes apparent in the course of the 1980s that the criticized restraint of the Ministry of Justice has another, more valid reason. By now, the Netherlands has over 13,000 children from the Third World who have been adopted by Dutch parents. The babies and toddlers from the adoption boom have become teenagers in the 1980s. Through the media, a perception of problematic cases arises as disillusioned parents of children who have been placed outside the home seek publicity. Sang is also placed outside the home. "At some point, things went wrong. Minor crimes and such," An remembers. She turns to Sang, saying, "Until you were drunk as a skunk in the cell and the police came to our door. That was the final straw. They turned it into an emergency admission." Sang says, "I was unbearable and unmanageable. Looking back, it had everything to do with my adoption. It is underestimated what it means to come here from an Eastern culture. The belief was and still is that you automatically do better here."

However, Liesbeth Graatsma, a social worker involved with the SIA from the beginning, emphasizes that in many cases, things have gone well. But she admits that there was too much optimism about the course of adoption in those early years. "We all thought those children were in a difficult situation, and there were no solutions in their country of origin. We had them here. So we wanted to help those children. We thought, it may take some getting used to, but it will work out. With patience and love, you'll get there. That's what later became known as the rosy bubble."

~

Koreaanse baby op Schiphol

De Olympische Spelen van ‘88

De druppel die de emmer deed overlopen

Met de negatieve berichtgeving in de media draait het positieve beeld over de internationale adoptie en daarmee daalt het aantal adoptieaanvragen fors. Tussen 1980 en 1989 zelfs met zestig procent. Naast de kritische geluiden in de pers, vermelden de eerste resultaten van onderzoek naar adoptie, bijzondere opvoedproblemen voor adoptieouders. Ook zijn de economische omstandigheden minder positief: de eerste grote bezuinigingsronde van de overheid doet zijn intrede.

Maar niet alleen de vraag, ook het aanbod neemt af. In Aziatische landen verandert de politieke houding ten aanzien van adoptie. De toegenomen welvaartsstandaard, in Korea van 248 dollar per hoofd van de bevolking in 1970 naar 2268 dollar in 1987, gaat hand in hand met een groeiend zelfbewustzijn. Binnenlandse adoptie wordt gestimuleerd en er komt een sterkere roep om het stoppenzetten van de ‘export van baby’s’.

In Korea wordt deze tendens gemarkeerd door de Olympische Spelen van ’88. Een jaar voordat de wereldschijnwerpers op Korea worden gericht vindt een politieke omwenteling plaats. In juni 1987 luiden studentenprotesten, stakingen en een massaal volksoproer het einde in van 25 jaar militair gezag. De nieuwe vrijheid van meningsuiting biedt ruimte voor een kritisch geluid, maar de adopties gaan onverminderd door. Eén jaar later tijdens de Spelen in Seoul presenteert Korea zich trots als een nieuwe geïndustrialiseerde democratie. Maar westerse journalisten grijpen de gelegenheid aan om een ander beeld van het land te laten zien en presenteren Korea als ‘s werelds grootste exporteur van kinderen. Het is de druppel die de emmer doet overlopen. Tijdens de Spelen verdwijnt geen enkel kind meer over de grens. En het jaar daarna is het aantal adopties significant gedaald. In Nederland van 107 plaatsingen in 1988 naar 13 in 1989. Korea lijkt van haar imago als baby-exporteur verlost. In Nederland vindt gaandeweg de jaren negentig weer een lichte opleving plaats in het aantal adoptieaanvragen. Inmiddels spant China de kroon. Maar nog steeds wacht ieder jaar een beperkt aantal Koreanen een nieuw leven in Nederland.

~

Korean baby at Schiphol

The 1988 Olympics

The final straw

With negative media coverage, the positive image of international adoption is shattered, leading to a significant decrease in adoption requests. Between 1980 and 1989, the number of requests drops by sixty percent. Alongside critical voices in the press, initial research results highlight specific parenting challenges for adoptive parents. The economic conditions are also less favorable, with the government introducing the first major round of budget cuts.

However, it's not just the demand that decreases; the supply also diminishes. Asian countries undergo a political shift in their stance on adoption. The increased standard of living, with Korea's per capita income rising from $248 in 1970 to $2,268 in 1987, correlates with a growing self-awareness. Domestic adoption is encouraged, and there is a stronger call to halt the "export of babies."

In Korea, this trend is marked by the 1988 Olympic Games. A year before the world's attention turns to Korea, a political transformation takes place. In June 1987, student protests, strikes, and a mass popular uprising bring an end to 25 years of military rule. The newfound freedom of expression allows for critical voices, but adoptions continue unabated. One year later, during the Seoul Olympics, Korea proudly presents itself as a newly industrialized democracy. However, Western journalists seize the opportunity to portray the country as the world's largest exporter of children. This becomes the final straw. During the Games, no child leaves the country's borders, and the following year, the number of adoptions significantly declines. In the Netherlands, from 107 placements in 1988 to 13 in 1989. Korea seems to shed its image as a baby exporter. In the Netherlands, there is a gradual resurgence in adoption requests during the 1990s. China now takes the lead, but a limited number of Koreans still await a new life in the Netherlands each year.

~

Sang de Klonia

De cijfers

Onderzoek naar gedragsproblemen

In 1979 wordt in Nederland voor het eerst onderzoek gepresenteerd naar adoptie van buitenlandse kinderen. Prof. Dr René Hoksbergen, bijzonder hoogleraar Adoptie, benoemt in zijn boek 'Adoptie van kinderen uit verre landen' specifieke opvoedproblemen. Maar harde conclusies blijven uit omdat de kinderen om wie het gaat nog te kort in ons land zijn. Pas eind jaren tachtig verschijnt het eerste grote landelijke onderzoek van kinderpsychiater Frank Verhulst. Zijn bevindingen leggen de problemen onomwonden bloot: buitenlandse adoptiekinderen komen vergeleken met 'gewone kinderen' vier maal zo vaak in aanraking met politie en justitie, ze volgen drie keer zo vaak speciaal onderwijs, het aantal uithuis plaatsingen ligt zes maal hoger en een kwart heeft professionele hulp nodig.

Toch spreken onderzoekers elkaar ook tegen. Zoals hoogleraar Femmie Juffer, zelf adoptieouder, die vorig jaar nog onderzoeksresultaten presenteerde die een einde moesten maken aan de vele mythes rond het onderwerp. Zij stelt dat buitenlandse adoptiekinderen weliswaar meer gedragsproblemen hebben dan niet-geadopteerden, maar dat de marges gering zijn. Prof. Hoksbergen zoekt juist geregeld de publiciteit om te wijzen op de 'omvang en intensiteit van de gedrags- en opvoedingproblemen'. Die zijn volgens hem 'vele malen groter dan bij in Nederland geboren kinderen'. Hij pleit nog steeds voor betere nazorg.

Maar wie het echt weten zijn de bijna 35.000 buitenlandse kinderen die inmiddels door Nederlandse ouders zijn, of worden, grootgebracht. Daarvan komen er 4.099 uit Korea. Aan Sang de Klonia, toen één van de eersten de vraag: Is het plezierig om geadopteerd te zijn? "Van mij had het niet gehoeven. Had mij maar daar gelaten. Wat er dan gebeurd was is een moeilijke vraag. Ik was waarschijnlijk dood geweest. Maar het gaat er om wat erger is: sterven van de honger of sterven van verdriet."

Tekst en research: Ariane Kleijwegt

Regie: Hein Hoffmann

Eindredactie: Laura van Hasselt

~

Sang de Klonia

The numbers

Research on behavioral problems

In 1979, the first research on the adoption of foreign children in the Netherlands is presented. Prof. Dr. René Hoksbergen, a professor of Adoption, highlights specific parenting issues in his book 'Adopting Children from Distant Countries.' However, definitive conclusions are lacking because the children in question have not been in our country for long enough. It is only in the late 1980s that the first major nationwide study by child psychiatrist Frank Verhulst is published. His findings openly expose the problems: compared to "ordinary children," internationally adopted children are four times more likely to come into contact with the police and the justice system, three times more likely to attend special education, experience six times higher rates of foster care placements, and a quarter of them require professional assistance.

However, researchers also contradict each other. For instance, Professor Femmie Juffer, herself an adoptive parent, presented research results last year aimed at dispelling many myths surrounding the topic. She states that internationally adopted children do have more behavioral problems than non-adopted children, but the differences are slight. On the other hand, Prof. Hoksbergen frequently seeks publicity to emphasize the "magnitude and intensity of the behavioral and parenting problems." According to him, they are "much greater than in children born in the Netherlands." He still advocates for better aftercare.

However, those who truly know are the nearly 35,000 foreign children who have been or are being raised by Dutch parents. Among them, 4,099 are from Korea. When Sang de Klonia, one of the first adoptees, was asked if being adopted is enjoyable, she responded, "I didn't need it. They should have left me there. What would have happened then is a difficult question. I would probably have died. But it's about what's worse: dying from hunger or dying from sorrow."

Text and research: Ariane Kleijwegt

Direction: Hein Hoffmann

Editor-in-chief: Laura van Hasselt

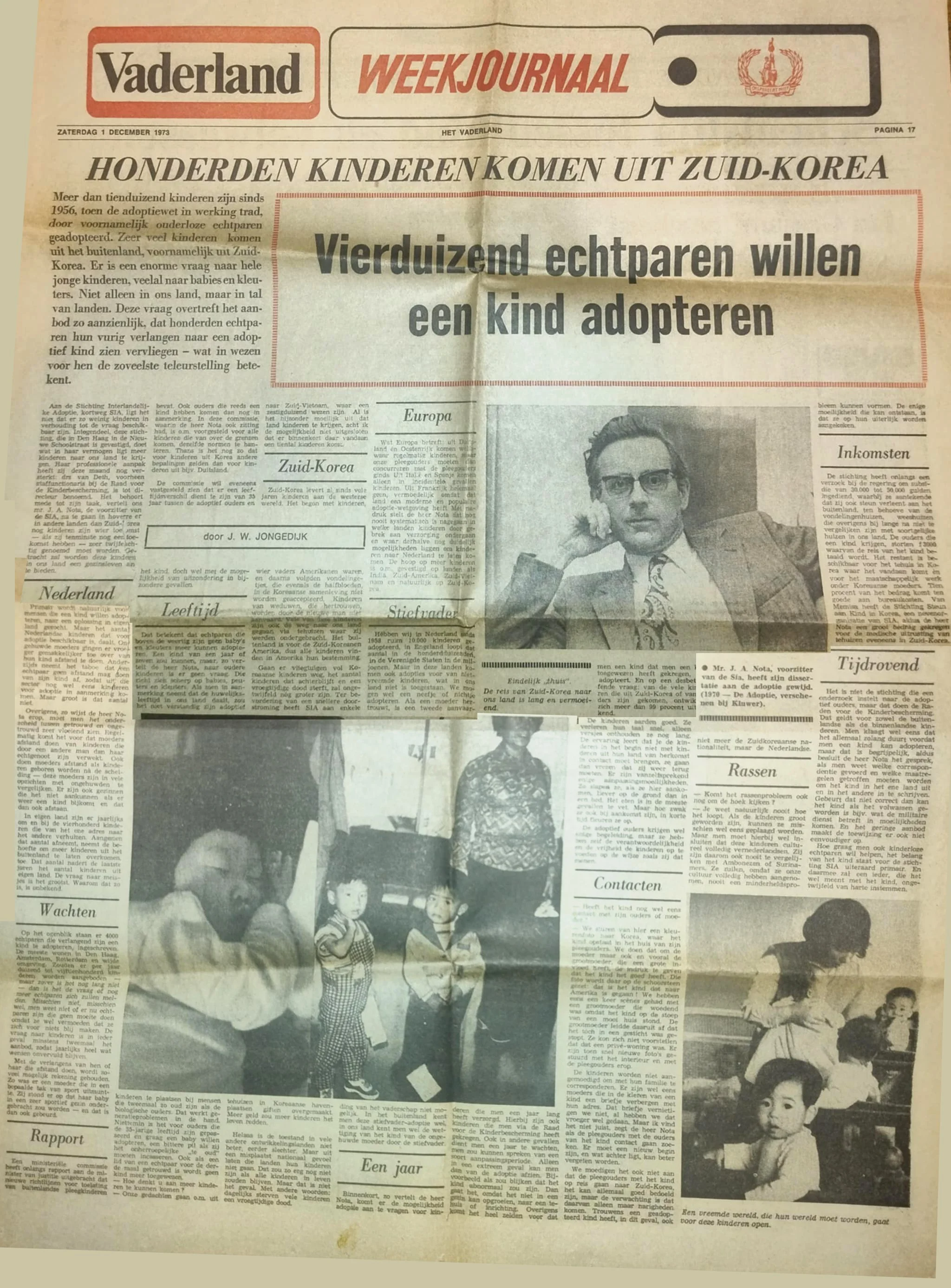

Dutch Article About Adoption: December 1st, 1973.

Thank you to a Dutch KSS Adoptee for sharing the following article photos! We have translated the Dutch text to English via ChatGPT. The translation may not be perfect, but it can give a general idea of the article content.

Different photos of the same article. We based our translation on the first set of photos (above this one).

To translate the text via Google Image and ChatGPT, we had to divide the two stitched together photos of the newspaper article into sections (1-10B). Please note that the translation below is for each of these numbered sections of the article. We have BOLDED the English text:

1:

HONDERDEN KINDEREN KOMEN UIT ZUID-KOREA Meer dan tienduizend kinderen zijn sinds 1956, toen de adoptiewet in werking trad, door voornamelijk ouderloze echtparen geadopteerd. Zeer veel kinderen komen uit het buitenland, voornamelijk uit Zuid- Korea. Er is een enorme vrang naar hele jonge kinderen, veelal naar babies en klen- ters. Niet alleen in ons land, maar in tal van landen. Deze vraag overtreft het aan- bod zo aanzienlijk, dat honderden echtpa ren hun vurig verlangen naar een adop tief kind zien vervliegen wat in wezen voor hen de zoveelste teleurstelling bete- kent. Vierduizend echtparen willen een kind adopteren

HUNDREDS OF CHILDREN COME FROM SOUTH KOREA

Since 1956, when the adoption law came into effect, more than ten thousand children have been adopted by primarily childless couples. A large number of children come from abroad, mostly from South Korea. There is an enormous demand for very young children, particularly babies and toddlers. This demand is not only in our country, but in many other countries as well. The demand far exceeds the supply to such an extent that hundreds of couples see their fervent desire for an adopted child fade away, which, in essence, means yet another disappointment for them.

Four thousand couples want to adopt a child.

2:

Aan de Stichting Interlandelij- ke Adoptie, kortweg SIA, ligt het niet dat er zo weinig kinderen in verhouding tot de vraag beschik- baar zijn. Integendeel, deze stich- ting, die in Den Haag in de Nieu- we Schoolstraat is gevestigd, doet wat in haar vermogen ligt meer kinderen naar ons land te krij- gen. Haar professionele aanpek heeft zij deze maand nog ver- sterkt: drs van Deth, voorheen staffunctionaris bij de Raad voor de Kinderbescherming, is tot di- recteur benoemd. Het behoort mede tot zijn taak, vertelt ons mr. J. A. Nota, de voorzitter van de SIA, na te gaan in hoverre er in andere landen dan Zuid-1 orea nog kinderen zijn wier toel omst - als zij tenminste nog een toe- komst hebben - zeer twijfelach- tig genoemd moet worden. Ge- tracht zal worden deze kinderen in ons land een gezinsleven aan te bieden.

The Stichting Interlandelijke Adoptie (SIA), based in The Hague on Nieuwe Schoolstraat, cannot be held accountable for the relatively low number of children available for adoption in relation to demand. On the contrary, the foundation has been actively working within its capacity to increase the number of children brought to the Netherlands for adoption. Recently, SIA has strengthened its professional team by appointing Drs. Van Deth, former staff member at the Council for Child Protection, as its new director.

One of the key responsibilities of the new director, as outlined by Mr. J.A. Nota, the SIA's chairman, is to investigate the availability of children for adoption in countries other than South Korea, particularly those whose future prospects may be deemed uncertain, assuming they still have the potential for a stable future. Efforts will be made to offer these children the possibility of a family life within the Netherlands.

3:

mensen die een kind willen adop taren, naar eem oplossing in eigen land gewocht. Maar het aanta Nederlandse kinderen dat voor adoptle beschikbaar is, daali. On gehuwde moeders gingen er vroe ger gemakkelijker toe over vah hun kind afstand afstand te doen. Ander zijds neemt het taboe dat een echtpaar geen afstand mag doen van zijn kind af, zodat uit die pectar nog wel eens kinderen voor adoptie in aanmericing ko- пно. Maar groot is dat aanial niet. Overigens, zo wijst de heer No- ta erop, moet men het onder- scheid tussen getrouwd en onge trouwd zeer vloeiend zien. Regel- matig komt het voor dat moeders afstand doen van kinderen die door een andere man dan haar echtgenoot zijn verwekt. Ook doen moeders afstand als als kinde- ren geboren worden nå de achel- ding- -deze moeders zijn in vele oprichten met ongehuwden te vergelijken. Er zijn ook gezinnen die het niet aankunnen als er weer een kind bijkomt en dat dan ook afstaan. In eigen land zijn er jaarlijks om en bij de vierhonderd kinde- ren die van het ene adres naar het andere verhulzen. Aangezien. dat aantal afneemt, neemt de be- hoefte om meer kinderen uit het bultenland te laten overkomen, toe. Dat aantal nadert de Inatste jaren het aantal kinderen uit eigen land. De vraag naar meis- jes is het grootst. Waarom dat zo it, is onbekend. Wachten Op het ogenblik staan er 4000 echtparen die verlangend zijn een kind te adopteren, ingeschreven. De meeste wonen in Den Haag. Amsterdam, Rotterdam en wijde omgeving Zouden er per jaar duizend tot vijftienhonderd kin- deren worden aangeboden maar zover is het nog lang niet -dan is het de vraag of nog meer echtparen zich zullen mel- den. Misschien niet, misschien wel, men weet niet of er nu echt- paren zijn die geen moeite doen omdat ze wel vermoeden dat ze zich voor niets blij maken. De vraag naar kinderen is in jeder geval minstens tweemaal het aanbod, zodat jaarlijks heel wat wensen onvervuld blijven. Met de verlangens van hen of haar die afstand doen, wordt zo- veel mogelijk rekening gehouden. Zo was er een moeder die in een bepaalde tak van sport uitmunt- te. Zij stond er op dat haar baby in een zeer sportief gezin onder- gebracht zou worden - en dat is dan ook gebeurd. Rapport Fan ministeriële commissie heeft onlangs rapport aan de mi- nister van justitie uitgebracht dat nieuwe richtlijnen voor toelating van buitenlandse pleegkinderen

People who want to adopt a child have sought a solution within their own country. However, the number of Dutch children available for adoption has decreased. Unmarried mothers used to be more likely to give up their child for adoption. On the other hand, the taboo against couples giving up their own child has lessened, so occasionally children from such situations are considered for adoption. However, this is not very common.

Furthermore, as Mr. Nota points out, the distinction between married and unmarried mothers should be seen as quite fluid. It is often the case that mothers give up children fathered by a man who is not their husband. Also, mothers sometimes relinquish children born after divorce—these mothers, in many respects, resemble unmarried women. There are also families that cannot cope with having another child and, therefore, give the child up for adoption.

In the country itself, there are around 400 children each year who are moved from one home to another. Since this number is decreasing, the demand to bring in more children from abroad is rising. In recent years, the number of children from abroad has come close to the number of children available from within the country. The demand for girls is the greatest. The reason for this is unknown.

Waiting

At the moment, 4,000 couples are registered and eager to adopt a child. Most of them live in The Hague, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and surrounding areas. If a thousand to fifteen hundred children could be offered for adoption each year, that would be ideal, but we're not there yet. It remains to be seen if more couples will register. Maybe they will, maybe not. It's unclear whether there are couples who are reluctant to apply, suspecting that they might be getting their hopes up for nothing. In any case, the demand for children is at least twice the supply, meaning that many wishes remain unfulfilled each year.

As much as possible, the wishes of those giving up children are taken into account. For example, there was a mother who excelled in a particular sport. She insisted that her baby be placed in a very sporty family, and that request was granted.

Report

A ministerial committee recently released a report to the Minister of Justice outlining new guidelines for the admission of foreign foster children.

4: